Interview with Maya Washington

Maya Washington is a filmmaker (writer/director/producer), actress, writer, poet, Creative Director, and arts educator. She received a BA in Dramatic Arts from the University of Southern California and an MFA in Creative Writing from Hamline University. Her work has garnered awards from Jerome Foundation, Minnesota State Arts Board, Minnesota Film and Television, and others. Maya is dedicated to projects that have a sense of “purpose” in the world, selecting stories that illuminate some aspect of the human experience that is untold, rarely seen, or might benefit from new approaches to issues of diversity and inclusion, primarily in America.

Terry Horstman grew up in Minneapolis and is the all-time lowest scoring basketball player in the history of Minnesota high school hoops. His work has been published or forthcoming from HeadFake, Flagrant Magazine, The McNeese Review, Taco Bell Quarterly, A Wolf Among Wolves, among others. He is a graduate of the MFA in Creative Writing Program at Hamline University and the executive editor of the Under Review. He is currently at work on his debut essay collection, which is shockingly about basketball. He lives and writes in Northeast Minneapolis.

This interview was conducted virtually and originally published as a podcast episode of ‘The Under Review Presents With the Call: a podcast on sports & writing’ on February 11, 2021. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Terry Horstman: My guest today is Maya Washington. Maya is a Under Review All-Star, author of the poem Get Your Racket Back, Keep Your Eyes On It, about the Saint Paul MLK Tennis Buff, which we had the privilege of publishing in our second issue and was one of our six Pushcart nominees from 2020. Maya is also the host of the podcast Light and Shadow, and the director of several films including the documentary Through the Banks of the Red Cedar, which will be published as a memoir this fall from Little A Books. Maya, thanks for joining me today.

Maya Washington: Thanks for having me.

TH: I want to talk about your film first and I was wondering if you’d be kind enough to give a little pitch on what Through the Banks of the Red Cedar is for any of our listeners who may not have seen it yet.

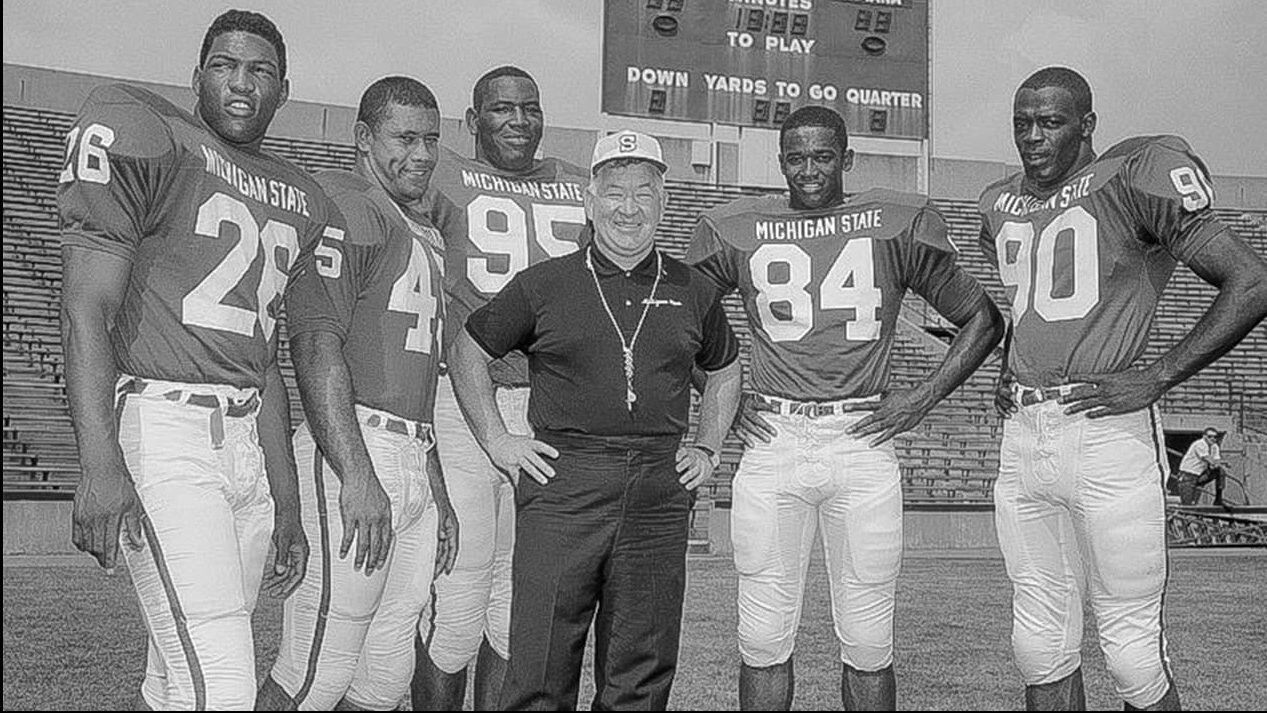

MW: Through the Banks of the Red Cedar follows my father Gene Washington, who played for the Minnesota Vikings in the late 60s and early 70s, and his experiences growing up in the segregated south before being recruited to run track and play football at Michigan State University at the peak of the Civil Rights Movement in America. What was unique about his team at Michigan State, is they were the first fully integrated college football team in America. So he and his teammates were from throughout the United States, but a number of them were African-American and recruited from the south. They went on to win back-to-back national championship titles, and my dad and three (of his Spartan teammates) were drafted in the first round of the NFL Draft in 1967.

It’s a story about family. It’s a father/daughter story. It’s a story about race and the ways that sports play an important role in changing and shaping culture. It’s about how my dad’s generation, and of course those who came long before them, really paved the way for the opportunities we see in sports today for people of all ethnic backgrounds, as well as women. There’s just a lot of important history there and that’s sort of what Through the Banks of the Red Cedar encapsulates.

TH: You mention in the beginning of the documentary that by the time you were born your dad’s football career was already completely over and that football wasn’t really part of your childhood. My first question is when did that change and when did the story of your dad’s historic football career get on your radar as a story you knew you wanted to tell?

MW: I’d say things really shifted for me in 2011. At the end of 2010, my dad retired from the business sector. My dad worked at 3M for most of my life. He was a guy who put on a suit and went to work everyday. He had this really great retirement party. Some of his former teammates from the Vikings showed up, like Joe Kapp, former Justice Alan Page, and I really got to hear a lot of great stories. Around that time he was also voted one of the 50 Greatest Vikings of All Time. So, this sort of shift in my dad’s life occurred when I was being introduced to some of his friends and teammates I never met because their chapter in history occurred before I was born.

Of course I knew Justice Page from growing up here in Minnesota, but Joe Kapp was not someone in my memory I had the opportunity to meet. Things really ramped up in August of 2011 when I had the great fortune to attend Bubba Smith’s memorial service alongside my dad and many of his (college) teammates. At that moment, it was the first time I was able to really hear that it was Bubba Smith who recommended my dad for his opportunity at Michigan State. I’ve sort of had this fantasy that these magical white men randomly found my dad in Texas, and as someone who loves history, it never occurred to me to try and piece together how that really happened, why that happened, knowing that everything was completely segregated in Texas, that a university would find him and bring him to Michigan State and give him this great opportunity.

So learning about that at a time it was unfortunately too late to thank Bubba Smith really sort of stung in a very personal way and a realization that every door that opened for my dad could be tied back to the Smith family. And of course every door that opened for me, tied back to them too. That really put me on this passionate dive into history.

My dad was voted into the College Football Hall of Fame also in 2011. Bubba Smith, and George Webster at the time, were two of the total four from that 1967 Draft Class, were already members of the National College Football Hall of Fame, and later (the fourth member of that draft class) Clinton Jones joined them. I just thought this was amazing and this important history with Duffy Daugherty, their coach, what sports historians and journalists called ‘The Underground Railroad of College Football,’ there was so much to uncover that I felt that film was the right avenue to dive into this history as a documentary from the perspective of me as my dad’s daughter.

It truly is, more than anything, a love letter to Bubba Smith and to his father Willie Ray Smith, who were really instrumental in my dad getting to Michigan State. And of course to all the pioneers whose stories people in your and my generation really don’t know because it happened before we were born. I’m just really passionate about documenting that history and offering a space for these very incredible men to tell their stories.

TH: I have friends’ dads’, whose favorite player was your dad. I’m just wondering without having the knowledge that he was this football star as a kid, were there ever interruptions when you were out in public of strangers coming up to your dad to talk to him, or get pictures, or autographs, or interact with him when you were just trying to have family time.

MW: Yeah I think my earliest memory of that happening, we were all out for a family dinner. I was really young so I don’t really remember the context, but I remember someone coming up to the table and asking my dad for an autograph. Really having no context for that, I think I was more excited about whatever restaurant we were at having frog legs. Someone ordered them and let me taste them and I just thought that was the wildest ever. To this day I don’t think I’ve had frog legs ever again. I think it’s funny that that memory coincides with that experience with my dad.

It was kind of weird because at the time I was coming up, it was more like people’s parents. My siblings were around (for his playing days), so their Gen X friends have those memories. There were a lot of situations where people were very nice to us. People were always saying hello and I just thought it was that my dad was a really friendly person and not because they recognized him, or thought it was pretty cool to meet him. It is really interesting I guess. It’s an interesting and weird experience.

TH: This documentary is also going to be released as your memoir later this year from Little A Books. I think what’s cool about this is you do often see books come out, getting optioned for film, and then being adapted into film. Maybe it’s more common than I’m thinking it is, but I feel like I don’t often see a film go the other route from a film to a book. Did you always know you also wanted to write the book version of this film? And what has that process of bringing it to the world in an alternate form been like?

MW: When I started my filmmaking career, I started as an actress and a dancer and started making films in 2011. My first film is a narrative short film called White Space. It’s about a deaf performance poet, who is performing for a hearing audience for the first time. Of course my first film being about poetry, it made sense for there to be storytelling across different platforms. That was always conceived of ‘okay, there’s this short film, I can see the benefit, especially in the literary community, of making sure that hearing poets and writers are partnering with deaf poets and writers and introducing the idea of having ASL interpreters at readings and performances so we can be more inclusive in that way.’ Also, it had a third component, well it kind of turned into four components. You have the short film. You have ASL interpreters at readings and not how we’re accustomed to seeing it in the American theater where the sign language interpreter is down stage right and off the stage and away from the action that’s happening. Just trying to re-invent what that might be if we had more inclusive live experiences. It was also visiting schools, sharing the film, doing residencies and educational workshops with young students and not-so-young students, college students as well. And the final component was a poetry anthology that had the work of deaf and hearing poets that I edited, as well as fine art.

Over the years it’s just sort of my M.O. as someone who dabbles in so many different art forms. It’s very surreal in 2020 seeing what’s happened with Covid and the extent to which everything has had to move to virtual spaces or the idea that we’re telling stories in hybrid ways now. This is something I was dabbling in like ten years ago. So it’s kind of cool to have a project of this scale be able to rise to this moment. With Through the Banks of the Red Cedar, even before the film finally came out, I had been doing artist’s residencies, educational touring, talking about these issues, talking about the desegregation of college football at colleges and high schools, a group of elementary school students were able to come out and see the film. I worked in collaboration with a couple of photographers here in the Twin Cities, Tom Baker and Hannah Foslin on a huge project with Hennepin Theater Trust when the Super Bowl was here. On Mayo Clinic Square, we had huge portraits, like huge 40-foot portraits of my dad, Carl Eller, Justice Page, along with quotes from the film. That was a big opportunity to have this storytelling in a public arts format, or in an urban art gallery so to speak, to just cover the side of a giant building in downtown Minneapolis with these ideas and these topics.

By the time an opportunity came to develop a literary component (to this story), maybe it was something that was in the back of my mind, but at the time I was just trying to continue to get the feature film out. Interestingly enough, the acquiring editor at Little A is a colleague and friend of mine, a poet named Hafizah Geter. In 2011, when my family attended my dad’s induction to the College Football Hall of Fame at the Waldorf Astoria, Hafizah kindly babysat my nieces in the hotel room above the ballroom where we were all attending the banquet. She had sort of been following me, following this story, at a time when I was not even aware that 10 years later I’d still be trying to tell this story. She approached me, maybe in the spring of 2018, and had been looking for manuscripts and reaching out to her network.

So I was like, ‘Hey, remember this movie I’ve been making forever? Don’t you think it would make a good book?’ And she was like, ‘Actually, I think it would.’

We continued that conversation and the rest is sort of history. It led to a proposal that was accepted. It’s been in the works for a couple years now and we’re racing down the tracks, which has been very fun and exciting to see the film have its first broadcast run and do that in the world as I’m making choices about what images to use for the book and moving into what will hopefully be publication in the fall of 2021.

TH: With the approach to the book then, something I’m thinking about in comparing books to movies, and what makes me excited that this is going to be a book is that there’s a lot of room to elaborate on things. You have more space for content in a book than in a 80/90-minute documentary. I am definitely someone who is more scared of editing than generating. Writing 2,000 words is a lot easier than writing 200 words for me. So I love the idea of getting to elaborate on every piece of story that’s here and pull out a bunch of threads, but I know not every writer is that way. Is that an element of the book that you were excited for, or was it a little terrifying?

MW: I think before I dove in it was so exciting because there’s just so much history. John Hannah for example, was the president of Michigan State throughout the time my dad was there, and for most of his tenure at Michigan State University as the president, he was the chairperson of the Civil Rights Commission of the United States of America. He was instrumental in a number of major legislations. Like Brown vs. the Board of Education, the Civil Rights Acts of 1964-65, and really had a very interesting role in how Duffy Daugherty was able to create a pipeline to the South and recruit black players. He had that support all the way up to the top of the university from President Hannah. To know that that was happening, while my dad was playing football and maybe occasionally the president of the university would make an appearance, you know how they do. To know they were in proximity to such major shifts and change and lasting impact is pretty remarkable.

Going down that wormhole, I was like, ‘Yes, this is so great! I can talk about John Hannah! I can delve into who the pioneers were before my dad.’ In 1913, Gideon Smith was the first black player at Michigan State. There were other black players throughout the Big Ten Conference. The history kind of quickly got overwhelming and became the hardest part. When you’re writing a historical narrative there’s things that I’m super excited about that visually you can, I don’t want to say cheat your way through, but you can kind of cut to the chase your way through in film, that in prose, wasn’t necessarily the case. If you’re going to go there (in prose), you’re really going to have to fully flesh out that storyline or that thread that you’re going down.

It’s far more interesting to not just think about that fact that exists, but the context around that fact and who John Hannah was as a human being and what the Big Ten Conference was. Even here in Minnesota, the University of Minnesota has kind of a challenging history and relationship to race. They’re sort of credited as pioneers, certainly (Coach Murray) Warmath and the number of black players throughout time before my dad, but they’re also responsible for the death of Jack Trice, who was a black player at Iowa State and was effectively trampled by the Minnesota Golden Gophers football team. There’s that kind of stuff that’s in the book that I’m really honored and grateful to shed light on because these aren’t well known stories in college football. I think telling them from the perspective of a non-footballer, hopefully gives an interesting perspective because of course I’m definitely more interested in the people. These are players, they’re figures, they’re stats, but they’re human beings who were going through different things in their lives and were very brave and noble. It has been incredibly daunting.

I would definitely say the amount of history and the amount of connecting threads has definitely been the hardest part. And as a poet, truly, writing this much prose is intense. I’m not going to lie. Luckily I’m passionate about the subject matter and I wrote the script for the film, but it’s definitely a new experience.

TH: Well, as a prose writer, [the idea of] writing poetry definitely terrifies me so I can understand the heebie-jeebies that come with writing in a secondary form. On a similar note, you work in pretty much every kind of artistic form that exists. It sounds like it was kind of a natural reaction for you to have at your dad’s retirement party hearing all these great stories, to think, ‘this would make a great film,’ then as the film got closer to think, ‘well, this would also make a great book.’ Do you usually have an ‘Aha!’ moment, or do you have a process for determining whether an idea would be a great poem, or film, or theater, or dance, or one of the many other things you do? I’m curious to hear the process for the appropriate form for each idea.

MW: There’s sort of an initial, ‘Aha!’ Whitespace was literally a dream. In that moment as you’re awakening in the morning and you hit the snooze button, but I saw it very clearly visually and it was literally a poet on their way somewhere and it culminates in a poetry performance. That was it.

That sort of told me this is a short film. I can’t explain it. I don’t know why, but it was a short film. I think, as an indie filmmaker, what seems to happen is the other components seem to reveal themselves as I move towards the target of the initial project or container. I have another narrative short film called Clear, and that is about a woman reconnecting with her family after a wrongful conviction. So that idea came to be because my friend and colleague, Tina Ngata Barr, was in her PhD dissertation process at the University of Minnesota. When she showed me what she wanted to do her dissertation on, which was re-entry benefits and resources for exonerated people, she educated me on how challenging that is. I assume when we see those news reports that someone’s been released from prison after 30 years for a crime they didn’t commit, and you see their family crying, you imagine they go have this steak dinner and get a big bag of money from the government, but unfortunately that is not the case. Many people fare worse than their counterparts who may have been guilty of the crime they were convicted of, or who may have served a full sentence and are eligible for certain re-entry resources. That was really fascinating to me.

As her friend and someone who lives in Minnesota, thank goodness we are blessed to have great public funding for the arts. I said to her, ‘I think this would really be a great film. I would love to see if I could write something and work with you to see if we could further educate people about this issue.’ I was able to get a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board for that project and it came out the same year that Through the Banks of the Red Cedar came out.

For me there’s the initial idea that comes in its own container. I knew Through the Banks of the Red Cedar was going to be a feature. I can’t tell you how I knew that, but I knew it was going to be a documentary and a feature documentary. Whitespace, I knew it was a short film and a narrative, and I knew Clear was a short film and a narrative. Oftentimes your road to getting that work funded, if you’re going the indie route, the path to building community, building an audience, for me everything I do has some kind of social impact or education component. As much as I enjoy making art and being around artists, I don’t just make art for myself. It’s just happened very organically that there’s always some kind of educational component and some opportunity for the community to engage in conversation about the issues that a film represents. It’s true storytelling with a purpose that the work is hopefully inherently entertaining, and interesting, and compelling, and has high artistic merit, but it’s really meant to exist in any place or space that people are where it can inspire conversation and dialogue or even action.

I love art and I love the ways you can tell a story through photography, film, literature, dance, theater, live performance, and public conversation and discussion. I think the arts are just a really great way for people who otherwise wouldn’t maybe be in an artistic setting, or artists who maybe aren’t exposed to a social issue, are able to have that experience through the work I try to create. I try to create an experiential witness to story.

Thank you so much again to Maya Washington for being part of Issue 04 of the Under Review. Pre-order Maya’s book, Through the Banks of the Red Cedar, today from Little A Books.